After leaving the comforts of Red Frog Marina, we set sail toward the largest island in the Bocas del Toro archipelago—Isla Colón, home to the provincial capital of the same name. We didn’t linger in the bustling town; after a quick resupply of groceries, we moved on, eager to return to nature and escape the noise.

Just around the corner lay our next anchorage: Big Bight, a calm inlet surrounded by dense mangrove forests. With little wind and short distances to cover, our pace was unhurried—more of a gentle drift than a sail. Snorkeling here didn’t offer much; there were no coral reefs in sight, and the water was cloudy, cloaked in the tannins of mangrove runoff. Still, the mysterious pull of the jungle ahead kept us curious and hopeful.

And the jungle didn’t disappoint.

At the far end of our trip, we were rewarded with not one, but two surprises.

First, we spotted a pair of dazzling rainbow-billed toucans, their oversized, colorful beaks cutting through the green canopy like splashes of paint. Nearby, an unfamiliar, almost prehistoric-looking bird caught our attention. After some research, we identified it as the smooth-billed ani (Crotophaga ani)—a jet-black, social bird with a croaky voice and a comically expressive face. It was a delightful discovery and a reminder of how rich and underappreciated this region’s birdlife truly is.

The second surprise was more human, but no less inspiring: The Plastic Bottle Castle.

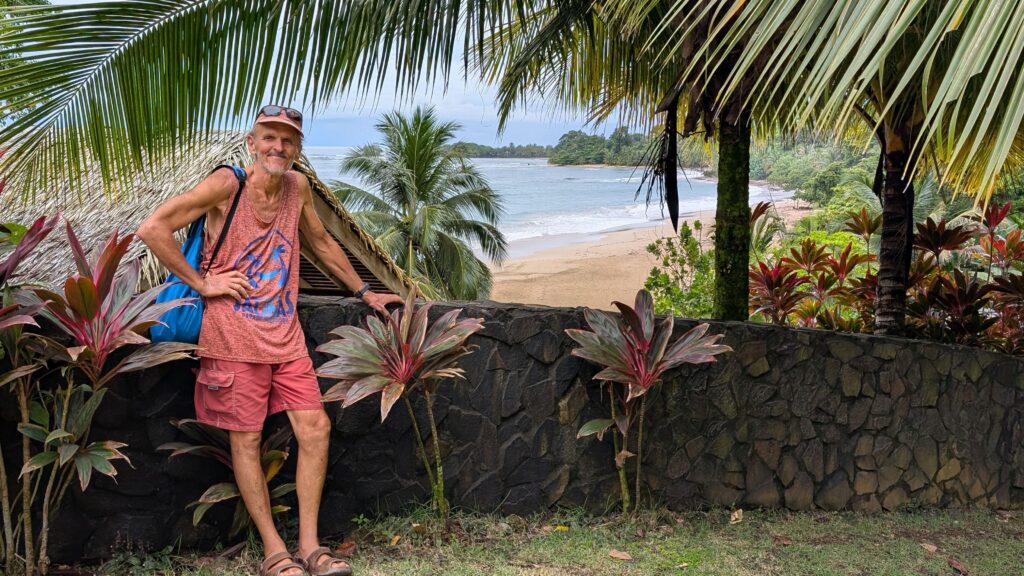

On a remote stretch of the island, we came upon a four-story structure built almost entirely from—you guessed it—plastic bottles. This architectural oddity is the brainchild of Robert Bezeau, a Canadian who moved to Bocas from Montreal in 2009. Like many newcomers, Bezeau was struck by the island’s biggest environmental issue: the overwhelming amount of plastic waste, especially discarded bottles.

With no organized recycling system in place, most of the waste is either burned—releasing toxic fumes—or worse, dumped indiscriminately into the landscape. Appalled but undeterred, Bezeau took matters into his own hands. In 2012, he began collecting plastic bottles with a bold vision: to change how people think about waste. And to do that, he needed something radical and visible.

So he began to build.

The first stage of his project was this very Plastic Bottle Castle, intended as the symbolic gate to a larger “Plastic Bottle Village”—a community of 120 homes constructed using recycled materials and concrete. The castle now serves as a museum and educational center, showcasing creative reuse and the urgent need to rethink our approach to consumption and disposal. A small water park for families was even added to help draw locals and tourists alike.

Unfortunately, the museum was closed during our visit, and we couldn’t speak to anyone directly involved in the project. Even the press seemed short on updates about the full realization of Bezeau’s dream. But one thing was clear: his message had already taken root. Awareness begins with a spark—and he lit it.

His work reminds us that changing minds takes time, especially when challenging ingrained habits and mindsets. But by transforming garbage into a palace, he proved that even waste can become a symbol of possibility—and a platform for education.

As sailors traversing these waters and running the Sail for Science project, we often reflect on how interconnected environmental stewardship and awareness truly are. Bezeau’s castle is not just a quirky landmark—it’s a call to action, a creative rebellion against apathy.

May we all carry that spirit forward—at sea, on land, and in every small act of preservation we choose to make.