Alexander Graham Bell – the distinguished polymath, renowned for his multifaceted contributions to science and innovation. He dedicated a substantial portion of his later years to scholarly endeavours at Beinn Bhreagh (, his esteemed estate and research center located in Baddeck.

Our expedition to Baddeck would have been incomplete without a pilgrimage to the Alexander Bell Museum, a hallowed ground in the realm of knowledge. Remarkably constructed and brimming with historical treasures, it stands as a beacon of intellectual curiosity. I wholeheartedly recommend a visit to this institution, where an assortment of artifacts and exhibitions awaits.

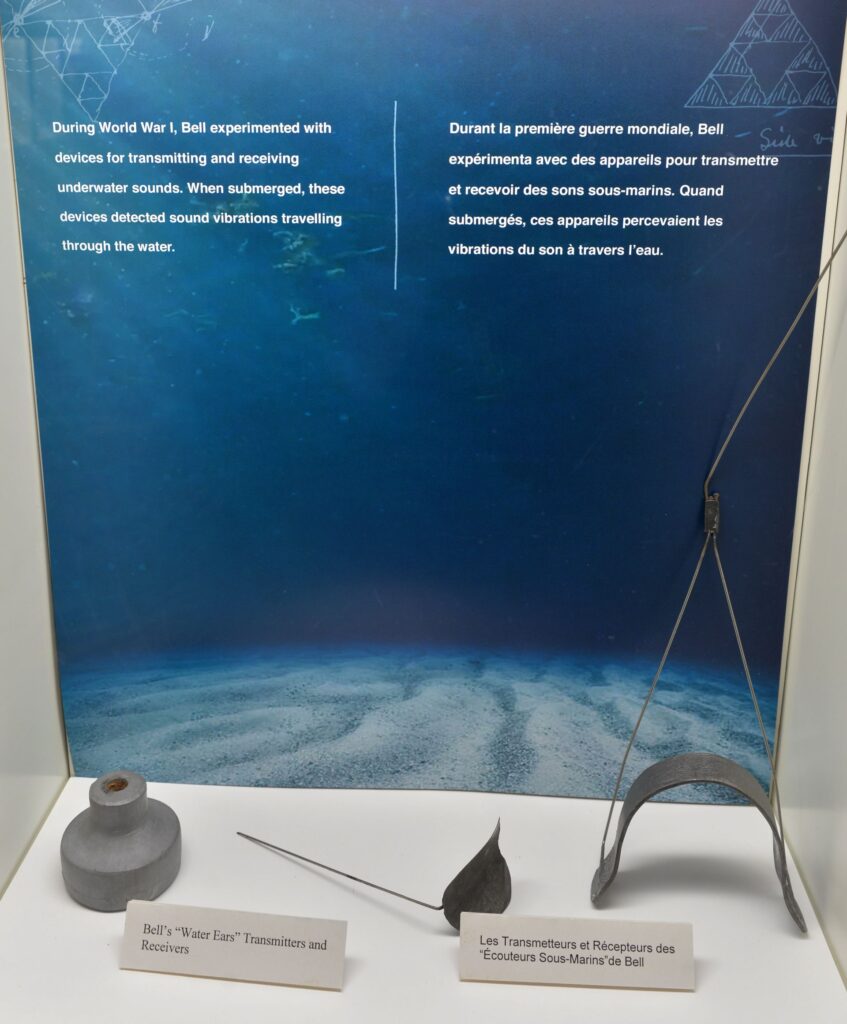

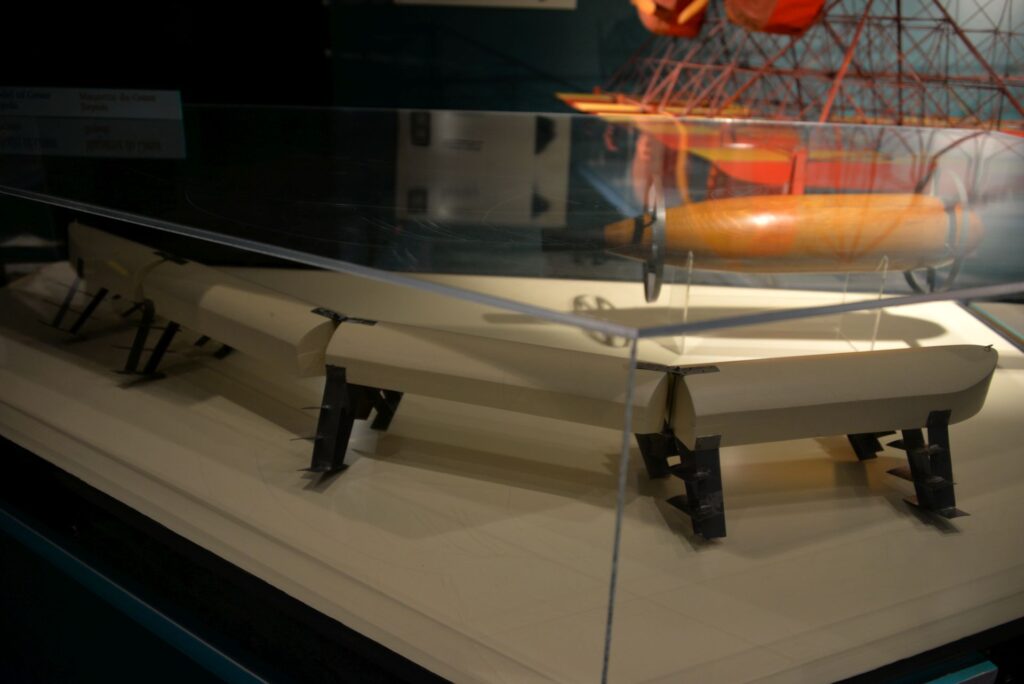

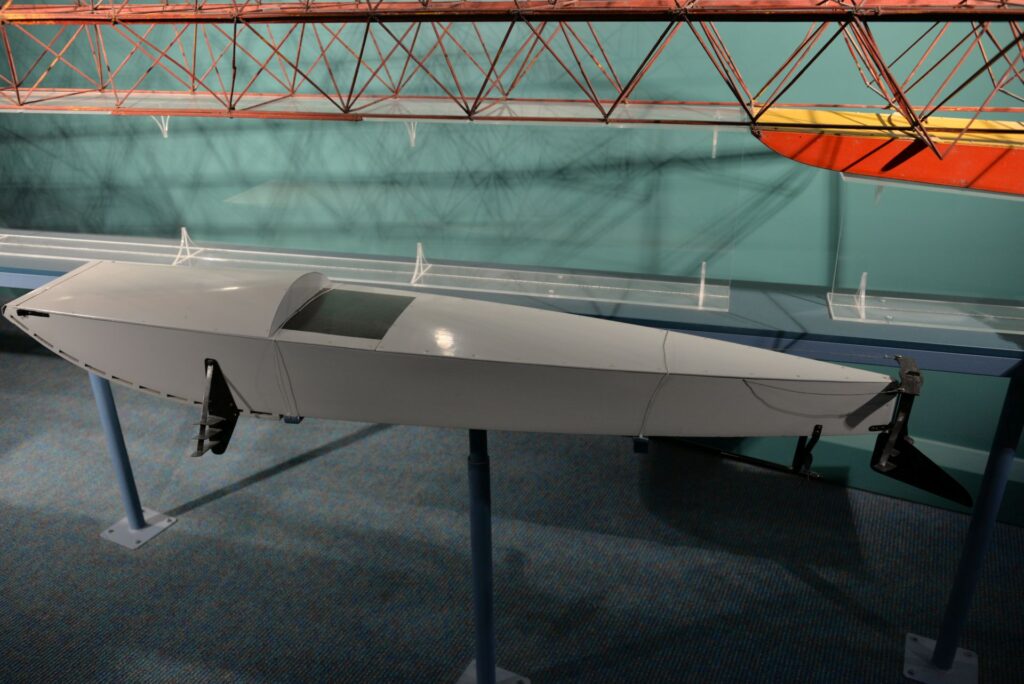

For us, practitioners of the marine sciences and sailors, the museum offered a captivating exploration into the realm of marine engineering. Among the intriguing exhibits, hydrofoils took center stage. A hydrofoil, for the uninitiated, assumes the form of a wing affixed to a watercraft. These foils, reminiscent of the wings of an aircraft, are engineered to facilitate the swift flow of water over their surfaces. At higher velocities, this hydrodynamic phenomenon begets lift, causing the vessel to transcend the aquatic medium and effectively levitate, encountering significantly reduced hydrodynamic resistance and enabling enhanced speeds.

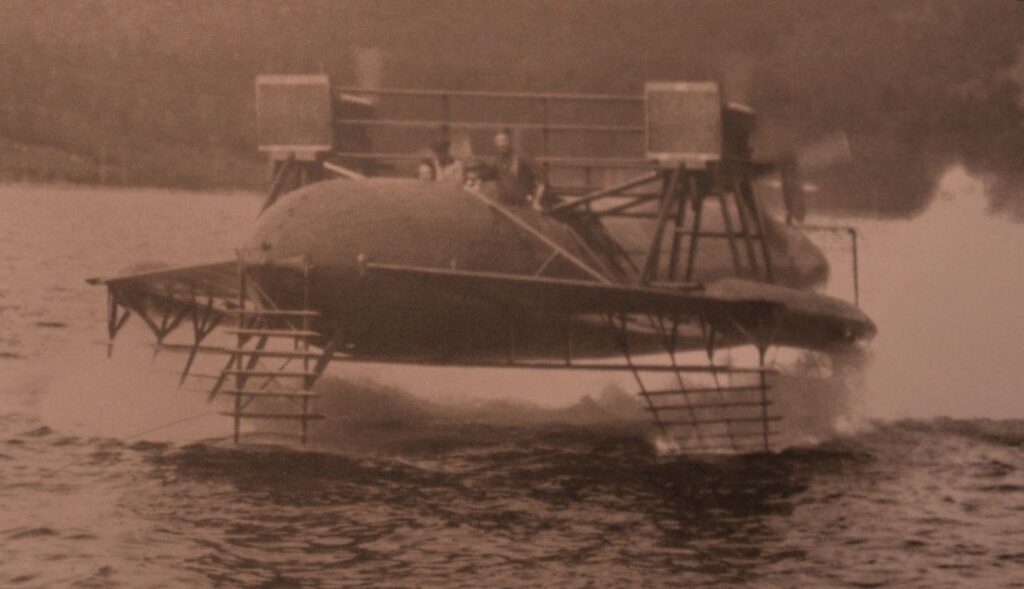

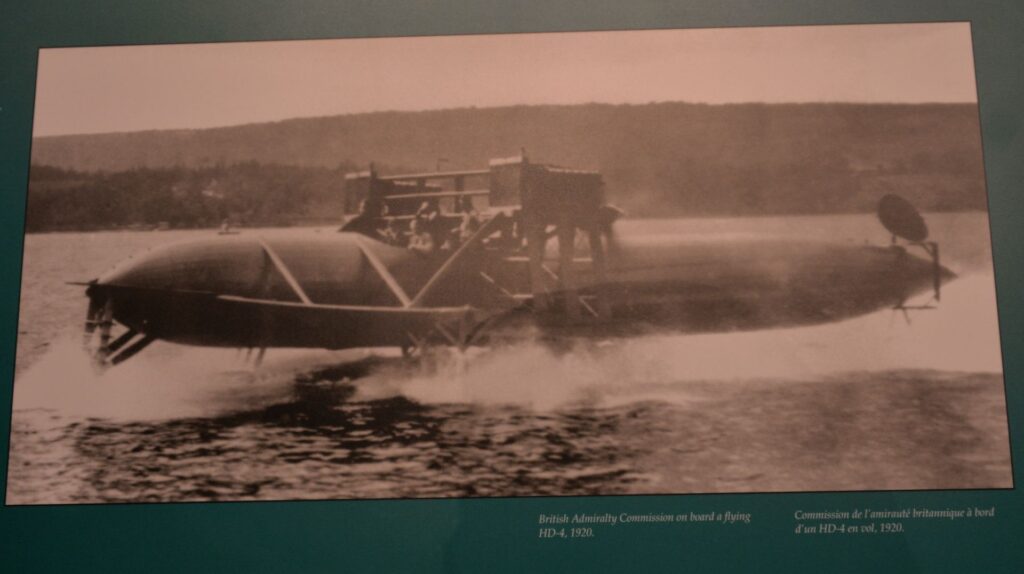

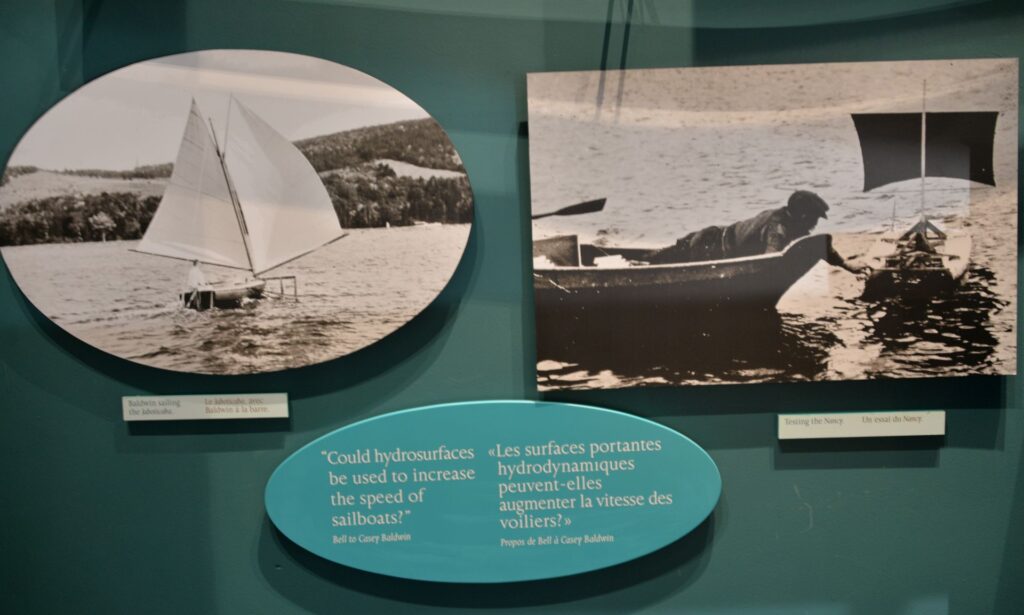

Commencing their hydrofoil odyssey in 1911, Bell and his collaborator Casey Baldwin embarked upon a remarkable journey marked by the design, fabrication, and rigorous testing of no less than four hydrofoil prototypes over an eight-year span. Their collective endeavours bore a resemblance to the epic sagas of exploration, albeit on the aqueous stage. Simultaneously, they pursued ancillary endeavours, including the incorporation of hydrofoil technology into sailboats, truly pushing the boundaries of maritime engineering.

Their pinnacle achievement, Hydrodrome #4, colloquially known as HD-4, etched its name in the annals of aquatic velocity. On September 9, 1919, it astoundingly traversed Baddeck Bay at an astonishing 70.86 mph, effectively establishing a world speed record for waterborne craft. This record, akin to a scientific lodestar, remained unbroken for the better part of a decade, underscoring the pioneering spirit and mastery of Bell and his associates. In the domain of aquatic locomotion, HD-4 reigned supreme, shattering hydrodynamic barriers and making profound contributions to the science of hydrofoils.

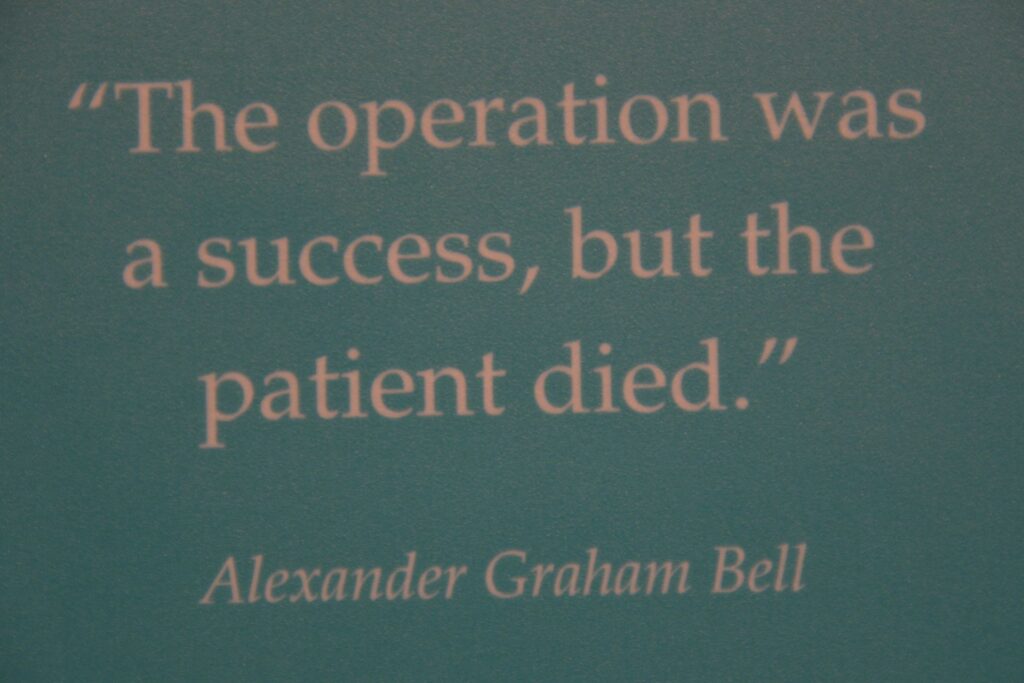

Unfortunately, by that time the First World War had ended and the demand for high-speed boats capable of catching German submarines had subsided. On 2 August 1922, Alexander Graham Bell died. Cassey Baldwin continued some experiments with hydrofoils at Beinn Bhreagh, but without commercial success, they were probably made before their technological time. This success passed late into the hands of Soviet shipbuilders – my entire childhood in Ukraine was next to flotillas of hydrofoils – Meteor. Voskhod, Raketa, Volga, which were widely used for high-speed transportation along rivers and seas.

But in the world of sailing, there are now a variety of hydrofoils onboard – from foil kitesurfing to IMOCA-60 and American Cup catamarans!

This is also worth mentioning:

Among his countless contributions, Alexander Graham Bell was among the original founders of the National Geographic Society. His father-in-law (Gardiner Green Hubbard) was the Society’s first president, and in turn, Alexander’s son-in-law became the first, full-time editor of National Geographic magazine. Alexander himself officially served as Society president and unofficially served as a kind of warm-hearted grandfather to the organization. When he died in 1922, the September issue of National Geographic ran a full-page tribute to “Founder, former President and senior Trustee of the National Geographic Society,” which included a distinguished photographic portrait of the inventor (Dr. Bell, as he was later known, was quite fond of photography and was instrumental in making it a priority of the magazine).

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/tweeting-place

Thank you, Yuri! Yes, Alexander Bell was a Man of many talents and endeavours. The founding of the NGS and photography among them- in a Museum shop I bought a book with Bell’s photographs – amazing vision!

The Silver Dart was not just the first heavier than air plane to fly in Canada, but the British Commonwealth.

Thanks for the comment! I did not tell the story of the Silver Dart, focusing more on the development of the Hydrodrome, which corresponds to modern sailing technology. But, of course, the Silver Dart was a remarkable achievement in aviation.