During our stay at Shelter Bay Marina, we had the unique opportunity to visit the nearby ruins of Fort Sherman—a sprawling coastal defense complex built by the United States in the early 20th century to protect the northern entrance of the Panama Canal.

Constructed just before World War I, Fort Sherman was part of a broader network of fortifications guarding the canal from both land and sea. Tucked away in the jungle near Colón, these overgrown ruins now stand as silent witnesses to a time when global powers invested enormous resources in defending strategic maritime routes.

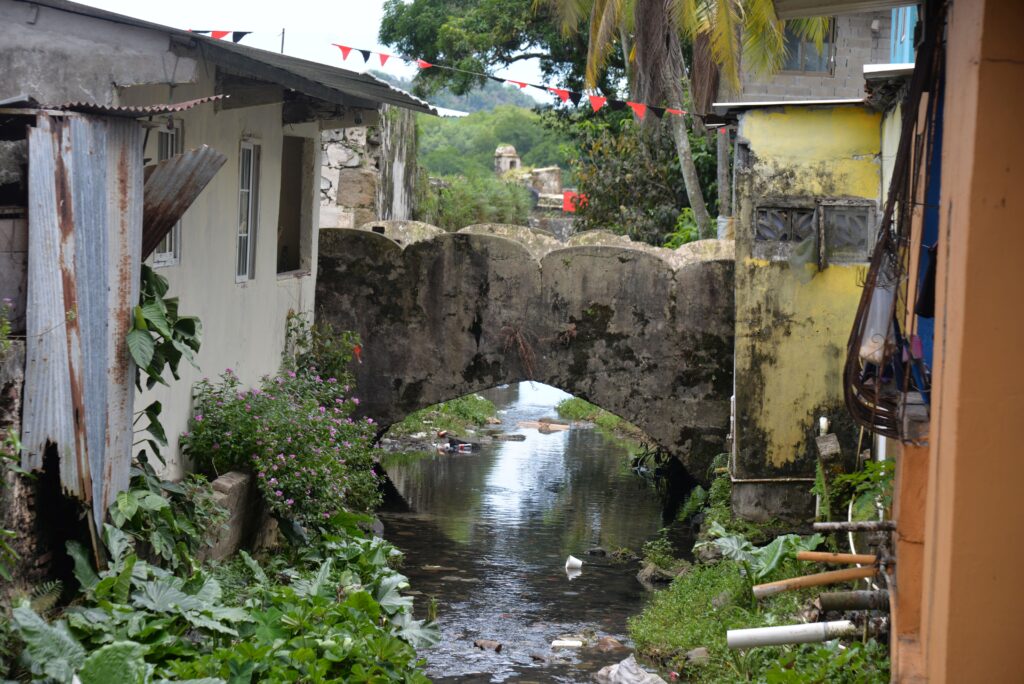

Walking through the site felt like stepping back in time. Concrete bunkers and massive gun emplacements—now slowly being reclaimed by the rainforest—hint at the scale and ambition of the original installation. Moss-covered walls, rusting rail tracks, and empty observation towers evoke images of soldiers stationed here to watch for threats from sea or air.

Though nature has taken its toll, the site retains a haunting beauty. Vines curl around the reinforced walls, and tropical birds now patrol where artillery once stood. It’s easy to forget that this peaceful, green space was once on high alert, guarding one of the most critical waterways in the world.

For us, the visit was both fascinating and sobering. The Panama Canal has always been more than a route between two oceans—it’s a geopolitical lifeline. Fort Sherman reminds us of the strategic importance of this narrow strip of land, and of the human effort once poured into its defense.

Today, Fort Sherman is largely abandoned, its history quietly fading beneath the canopy. But for those who take the time to explore it, the fort offers a powerful glimpse into the military past of the Panama Canal Zone—and a chance to reflect on how the world’s priorities have changed.