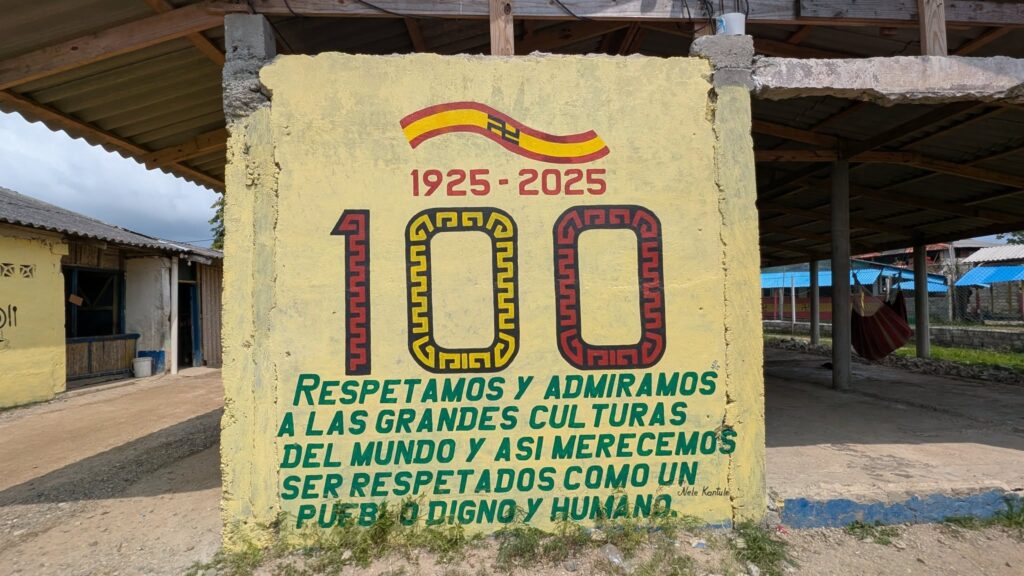

As SV Oceanolog continued her northward journey along the coast of Panama, we found ourselves dropping anchor near a large village—no, more accurately, a city—nestled within the Guna Yala territory. The place was Ustupu, the largest settlement in the Guna region and the birthplace of Nele Kantule, one of the most revered leaders in Guna history and a key figure in the 1925 revolution that secured the Guna people’s autonomy from the Panamanian government.

Stepping ashore felt like stepping into a different world. Ustupu is built across several interconnected islands, with wooden footbridges linking the land like a patchwork of dreams. The buildings are mostly traditional huts with palm-thatched roofs, but here and there, you’ll find concrete structures—signs of the slow and inevitable march of modernity. Despite the creeping changes, the cultural essence of the Guna people feels unshaken, pulsing steadily beneath the surface.

We had come not just to restock our food supplies, but also to immerse ourselves in the daily rhythm of this unique society. And yet, as with many remote corners of the world, communication posed its own set of challenges. The Guna speak their own language—Dulegaya—and although Spanish is sometimes spoken, English is rare. Our conversations quickly became a mix of hopeful gestures, animated facial expressions, and pointing fingers, which, while endearing, were only partially effective.

Still, communication isn’t always about language. It’s about intention, about showing respect, curiosity, and a willingness to listen. Through these shared cues, we began to understand more than we expected. A friendly elder, watching us fumble through our “point-and-hope” dialogue, eventually brought over a young woman who spoke some Spanish. With her help, we asked about buying fruit and vegetables—and discovered that supplies were limited. Most of the Guna rely on fishing and small garden plots for sustenance, and goods like rice, flour, and oil come on supply boats that don’t run on a strict schedule. We managed to purchase a few essentials: sugar, crackers, bananas, a couple of cucumbers, and some onions. A modest haul, but every bit felt precious.

Wandering the narrow paths of Ustupu, we were struck by the remarkable sense of community. Homes were built close together, often with shared walls. Children played in the alleys with makeshift toys, and groups of women in vibrant molas—the traditional Guna blouses, beautifully hand-stitched with intricate patterns—gathered to talk and laugh under the shade. Hammocks swayed in open-door homes, offering both comfort and a symbol of daily life in a place where simplicity and tradition reign.

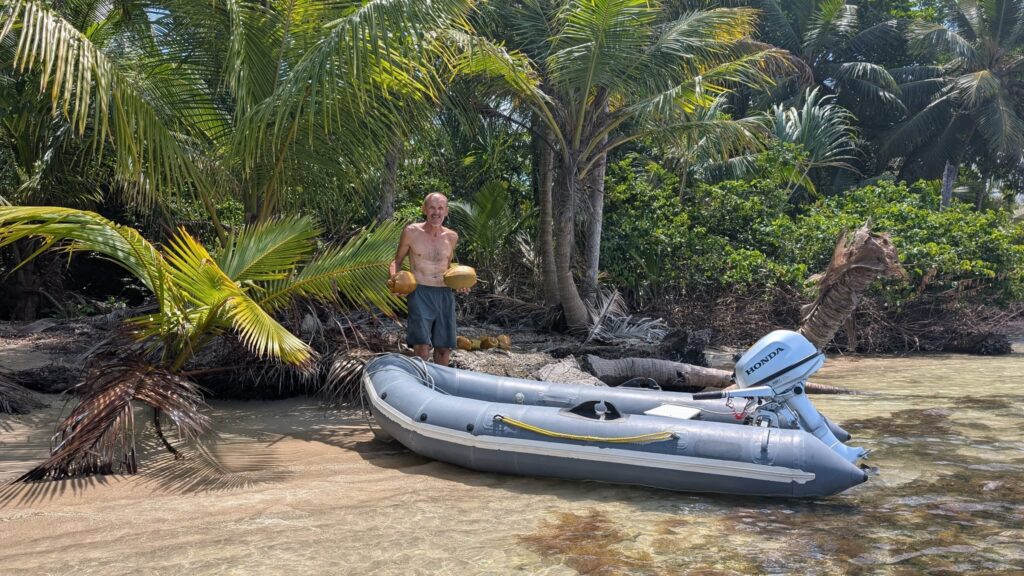

What stood out most was the egalitarian spirit. There was no sense of hierarchy or materialism. Everyone seemed to live on equal terms. There were no cars, not even bicycles. Transportation consisted mostly of ulus—dugout canoes carved from mahogany, gracefully cutting through the water under the rhythm of hand paddles. These boats are used for everything: fishing, trade, commuting between islands, or heading to the mainland to tend to gardens or gather supplies.

Ustupu is more than just a village; it’s a stronghold of Guna identity. The legacy of Nele Kantule lives on here, not just in monuments or stories, but in the continued autonomy and unity of the people. He helped shape a vision where the Guna would control their own lands, preserve their traditions, and make decisions through their own political councils. That vision remains intact nearly a century later.

Leaving Ustupu, we felt both awe and a touch of melancholy. It’s a rare thing to witness a culture so deeply connected to its roots, and rarer still to experience it with such intimacy. Yet, like many indigenous communities, the Guna face a future filled with uncertainty. Climate change, emigration, and creeping modernity pose threats not easily held off by strong will alone.

Still, as our anchor came up and Oceanolog turned toward her next destination, we carried with us a renewed sense of respect—for the sea, for the cultures it touches, and for the people who call these places home. Ustupu had welcomed us in its own quiet way, and we were grateful to have been its guests, even if just for a short while.